My course is run and I am no longer a seaman. I am a landsman again. These two sides of living have always been apart, so while a seaman temporarily on land is still a seaman, a landsman, even one who is a stolid passenger on a ferry or cruise ship, is still a landsman. Making your way of life upon the sea is a dedication that changes your state from the one to the other. Making your way of life upon the land, as retired sailors must, changes you back again.

I had understood this long ago, when I first planted my oar so far from the sea that I had come near to it on the other side of the land. When I gave up the Merchant Service, I had like Gawayn, wandered into the wilderness of Wales, and I found a tiny university to perch in, a miniature Oxbridge college, set like a semi-precious stone in the unimpressive shaley country rock of central Wales. Where shall I wander now?

Before I answer that question in the best way that I can, I must first relate the happenings of my last week at sea, in which as it happened, I was the only trainee Coastal Skipper on board. This meant that I was able to act as skipper myself, mostly under the watchful eye of the instructor, for the whole week. I also had some responsibility to support and assist in the training of the only other trainee, a dependable young Canadian farmer on the Competent Crew course which I had completed myself six weeks earlier. Here he is receiving his certificate, at a full 6 foot 6 inches, dwarfing the instructor.

Bumps & Grinds

This was what the instructor called the harbour exercises he set me, but had I actually bumped his boat, or ground it against the quay, I can hardly believe that any skin at all would have been left on my back, for he had a voice more effective than the cat o’ nine tails.

An invaluable lesson he taught me at this time is to use nature to assist in moving from a quay. If wind is king – when the current is none or negligible – then move away from the quay to take advantage of its direction. That is to say, back off the quay if it blows forward of the beam. If tide is king – and if there is any it can easily take precedence over wind – then choose the tide’s direction to move in. In both cases vice versa for the other case – i.e. go off forwards if governing wind or current is abaft the beam.

I found myself to be very confident in turning the boat under engine power within its own length. To do this it is first necessary to take account of ‘prop wash’. This is the tendency of a single propeller to turn the boat sideways and in most boats the bows turn to starboard. This means that it is much easier to turn to starboard than to port because the prop wash helps you to turn in that direction. With judicious use of forward and reverse drive it is possible to keep the boat gently turning, within its own length, indefinitely. This can be very useful if your crew needs some extra time to complete some evolution, such as setting out the fenders ready to go alongside.

Another operation which is slightly different in every boat, according to the shape of its side, is the approach to a quay under power. In the particular boat in which I had the temporary privilege of command it is necessary to line up the aspect from bows to beam parallel to the dock and drive straight towards it at harbour speed, that is just sufficient to provide steerage way, more than one knot and less than two. When the boat is frighteningly close to the dock it is necessary to turn the bows away and bleed off the remaining speed letting the boat come alongside and then be controlled to stay absolutely stationary.

To determine whether it is moving it is important to look at reference points in the surroundings, and not to rely, as I initially tended to do, on the speed instrument as this only displays the speed through the water, not the speed over the ground.

the Royal Phuket Marina (RPM) is located about half way down the east coast of Phuket island and access from the open sea is via a winding channel marked by posts and it is remarkably shallow. For a monohull sailing vessel with a keel there is only a short period of time either side of high water when there is sufficient water. When we had finished our bumps and grinds, we had reached the beginning of this time for the time and height of tide predicted. Depending on the height of tide at the time the period of grace for our vessel was just an hour either side of high water.

Before setting off we became aware that steam was being discharged from the engine instead of water, which indicated that circulation of cooling sea water was insufficient. No damage had yet been done, but the rising temperature from the exhaust indicated a probable intake blockage, and so it proved. There was an inspection cap in a tube vertically above the intake, below the waterline. When the cap is removed, therefore, sea water should gush out, but none came. By poking about we determined that a piece of rotting organic material from the harbour bottom had blocked the intake and we had to improvise a tool to clear it, by pushing it down from the inspection cap. This took us almost to the time of high water, dangerously close to the time when we must attempt the shallow passage outside the marina on a falling level of tide.

Pilotage

Control of the vessel between open water and harbour is known as ‘Pilotage’, and this part of the voyage out of RPM is pretty easy, as you just have to follow the long series of white posts, keeping them on the starboard hand about a boat’s length away.

This aspect of navigation is often supported by a wonderful book also known as a ‘Pilot’, which provides detailed information about almost every point of interest within the coastal waters which it covers. Not for the first time I thought of Chaucer’s Shipman

He knew alle the havenes, as they were,

Fro gootlond to the cape of fynystere,

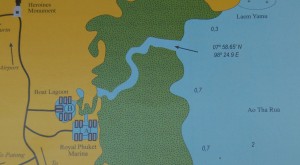

Here is the chartlet of the approaches to RPM, containing the information of the type that the Shipman had to carry in his head.

This very useful view shows land and sea information. You can see the twisting course of the navigable channel, which the text in the Pilot book advises you is marked out by the white posts. The position of the start of the posts is also noted on the plan as you can see above (lat/long).

This channel is the place where my previous instructor had asked me to watch his stern for disturbed mud, in case he was ‘ploughing’, but then he was in command, and I could afford to sit back a bit and relax. Now it was I in command and I had been pretty nervous until the instructor advised me that if we did take the ground – which here is soft mud – then on a rising tide we could just have a cup of tea while the boat lifted off naturally with the increasing depth. With a gulp I realised that this safety margin was almost used up in the present case.

Here is a snapshot of that earlier inward passage.

You see the line of posts on the port hand, stretching away towards RPM under the conical hill in the distance.

Although the yacht in the picture above has 4 inches less draught than my later command, the tide level was nearer to ‘Springs’, the bi-monthly higher tides that occur with moon and sun pull in conjunction, so the level of high water was about a foot higher than on that inward passage.

We experienced no problems, and always saw a small value on the depth sounder set to keel depth. We reached the end of the channel without incident and set course for open water.

Voyage to Ao Nang

By the time we cleared the posts it was windless and almost dark, so the voyage to the mainland on the other side of the gulf of Krabi was not particularly inspiring. A glance at the map below will show that we just needed two legs, a southern and a northern to reach our destination.

We had to travel from just above the word ‘Phuket’ past the island whose southern tip is obscured by the ‘e’ in Phuket, to the bay to the left of Krabi, which is called Ao Nang.

A portion of the small scale chart of the area looks like this.

As we motored southwards the heavens opened and although I put on my light anorak (bought on the M25 motorway) and my bicycling trousers, I was soon wet through and shivering – yes shivering in the tropics! I was extremely relieved to call the instructor and his wife three hours later to do their watch, and doubly grateful when I discovered that they had not called us on arrival at the destination towards the end of their watch, so the anchorage at Ao Nang was blessedly done for me!

Krabi region

The next morning, after breakfast, we launched the dinghy which had been sitting upside down on the foredeck and motored into the beach so that we could do shopping in the little town. Already the land heaved when I went ashore! This strange feeling even happens after a voyage in a 45,000 liner, so I was not surprised.

Returning to the boat just after noon we set off still under engine power to a nearby island where there is the most beautiful coral reef I have ever seen. After a rather disconcerting GPS experience of apparently sailing directly over land, we found an anchorage off the reef, and clambered into the dinghy with flippers, snorkels, and masks.

Oh the profusion of underwater life, and the colours! Most impressive of all for me were giant clams camouflaged to look like reef, with patches of indigo, yellow, and red, but actually concealing powerful jaws that would close on any fish foolish enough to tempt the sensitive lips. Many multi-coloured fish darted clear of the jaws, acrobatic in their element.

Once we were back aboard, the sky darkened again as it so often has in an unseasonal way during my time in the Andaman sea. We were able to sail off the mooring in a re-creation of the conditions in which the other boat had gone aground. The instructor was at pains to describe exactly how it should be done, by waiting until the rythmic swinging of a boat at anchor comes onto the right tack, and then showing a bit of foresail (backed by hand if necessary) to ensure that you can sail off away from the direction of the reef.

Shortening sail to meet the squally conditions we proceeded to a nearby piece of the mainland which is only accessible from the sea, due to the mountainous terrain hereabouts. A complete village for backpackers has been built with everything brought in by boat. We had a memorable fish dinner in the end restaurant, right up against the sheer cliff that makes this piece of terrain inaccessible from the land side.

Pilotage to the Sea Gypsy Village

Another night of peaceful sleep was mine before I had to attempt the difficult pilotage right up to the apex of the gulf shown in the chart above, threading through the myriad islands to the Sea Gypsy village built on piles against an island too steep for human habitation. This pilotage was something of a feat of seamanship and I like to think I did not do too badly although I did make at least one serious mistake.

The key to safe navigation in these waters is island identification, and by God you have to have your wits about you. As was often the case in these voyages there seemed not to be enough time to take in all the details of the charts before starting, and so I experienced a constant need to go below so that I could reassure myself about where we actually were.

Having at length found what I believed was my proper channel, I headed for an island that I dubbed ‘Hovis’ due to its rounded loaf-like shape. As we came towards it I should have been alerted to the fact that it was much further away than it ought to have been if it was the island I was seeking as my next ‘Way Point’.

The instructor had earlier told me that a ‘massive system failure’ had caused a malfunction in the GPS, so this avenue of navigation was firmly closed to me, and its lid fixed on top. Unable to relinquish identification of Hovis as my Way Point, I proceeded towards it, giving myself the spurious explanation that the tide had pushed us back to account for its comparatively great distance from us.

Alas, we had passed the real island, which if I had been awake, I would have seen lurking next to the last headland, both in reality and on the chart. The instructor put me right with some acid words and difficult questions like

“Why are you off course?”

to which the only answer was

“Stupidity, sir, sheer stupidity.”

I have a feeling this rather 18th century language (mis-quoting Sam Johnson again) may have been irritating.

With very great patience the instructor told me to mark our ‘Dead Reckoning’ position on the chart. This means drawing a line in the direction of the course steered from the last known position at which the ‘log’ of distance travelled through the water was noted. The length of the line – i.e. the distance – is calculated by the well-known formula of speed over time. I found the ‘DR’ position – marked by drawing a short line across the course – was further ahead than I had thought, but I did not believe it!

Instead I foolishly continued to believe in my incorrect identification of ‘Hovis’ despite having two clear indications to the contrary! What a fool! It was a valuable lesson.

After some anxious minutes while we regained our proper track and the rest of the pilotage passed without much incident, but with a great deal of sweat and fear of danger. I should have been spending 95% of my time on deck and 5% below at the Chart Table, whereas my actual proportions where the reverse, said the instructor.

We arrived at the anchorage for the Sea Gypsy Village – shown in the Pilot book at point ‘A’ – as the sky darkened again. This time there was a thunder storm apparently overhead. The brightness of the flashes was blinding and the apparently simultaneous thunder was louder than I have ever heard before. It was beyond terrifying. While the boat’s owners sheltered behind the canvas dodger, the young Canadian farmer and I were on deck when the mainmast took a glancing blow from what was probably a slight leak out of a massive forked bolt that struck the sea or the land somewhere very close. The cockpit display of the values detected by the wind instrument mounted on this mast went blank at this point.

Another soaking! but how good the dinner tasted after getting warm and dry again.

The Pilot book had said to anchor at point ‘A’ in 4-5 metres of water, and the place I found had 4.8 metres at the current tide level, so I thought this good, but did not have time, due to the storm, to work out what the level would be at low and high water. That night I awoke suddenly at 0300, just after the time of low water, and looked at my watch with my torch which I always kept beside it, and I noted the time with a sickening realisation until I reasoned that although my awakening was a little late, we were not aground.

I later learned that the instructor had a better body clock which roused him from sleep before low water, and that he had got up to witness that the least depth of water below the keel for that tide was in fact 0.7 metres, a reasonable if slim safety margin.

In the morning the storm was only a distant memory. Here is a shot of the village itself.

Return to Phuket

I quickly returned to blessed sleep in preparation for the continuation of my pilotage, now threading back towards the south of Phuket again.

“Have you ever fired a rifle?” I was asked.

“Yes”, I replied.

The instructor used this experience to show how you could use one island behind the passage between two others like the foresight and backsight on a rifle, and keep them equally spaced as the boat proceeds down a track between dangers on either side.

If the gap between the distant island and the starboard island starts to close, you steer to starboard, or to port if closing to port. This is an excellent tip which can be used where a course based on such an alignment is the one you need to follow. Bearings taken on objects which you pass can be used to determine whether particular dangers, rocks, wrecks, reefs, sand bars and the like, have been passed.

All day we passed through narrow channels set in extraordinary seascapes. This is the area of ‘James Bond’s Island’ and here are three photos showing what the limestone terrain is like in the region.

The day was completed by landfall south of Ao Chalong, the southernmost port on Phuket. We anchored again, this time off a very exclusive hotel where we were welcomed for happy hour before taking another memorable sea food meal on the nearby beach.

Here is a photo of the boat at anchor, taken from the shore.

Harbour evolutions

The next morning I navigated my first complete passage through a buoyage system in daylight, from the safe water mark to the last channel marker. We went into the half-built marina set at the end of a half-mile long pier at Ao Chalong to have a look, and came out again to do more harbour evolutions.

One exercise which both my aspiring ‘Competent Crew’ and I took was to sail a figure of eight course around two buoys in both directions, thus passing through several tacks and gybes with the intention of passing each buoy within a boat’s length.

Then we returned to the marina under sail and entered. Then we started the engine and hovered head to wind to get the mains’l down. I then drove up to the mooring position on the dock indicated by the instructor and gently brought the boat to rest beside the pontoon on which we finally moored at the end of my course.

It then only remained to re-do the chartwork examination in which I had performed so poorly during my classroom course two weeks before. This seemed to take up a lot of the remaining time before dinner ashore when I said goodbye to old shipmates including Mr Brash and the other two instructors.

Sea change

The next morning I left the ship and was awarded my certificate. I became a landsman again, so now it is time to explain whether this experience has been life-changing.

On a practical level I now possess the qualifications that enable me to charter a boat and I have the experience needed to sail it safely within 60 miles of the shore, by day and night, in tidal waters. That is potentially life-changing because it opens an opportunity to spend time at sea which beforehand did not exist for me. However, although this is important, it is not really the main story, which is more closely interwoven with my inner man.

This man has been balanced by the whole experience of the six weeks at sea, under intense instruction. I first felt this and described it when considering how my new appreciation of the tidal changes in the sea were mirrored in my spirit, or soul. It is that strange sense of being with Phlebas again, the tall, handsome, drowned Phoenician sailor who has accompanied me on all my voyages and who has been given up by the sea to my view as at the end of days she will give up her dead, and perhaps we shall all proceed to judgement.

Another change, but one for which I cannot account is the overwhelming desire I now feel to cast aside all doubts and hesitations and write the story which I shall be calling ‘Old Enough’ so as to make clear some incontrovertible truths and to publish them.

If i were forced to give an explanation of this I would say that the life that sailors lead is on average simpler and more honest than that of the landsman. For the sailor living by skill and permission on an alien element, depends on interpretation of the broad sweep of the horizon, and on his reading of the clouds, and his partial prediction of the mysterious movement of the restless waters. Relying on these interactions is humbling because the forces to which he he is exposed are so powerful and so dangerous. Instead of jostling his fellows for slight advantage of position or money, he deals with the clean and perilous giants whose domains he must pass to reach his harbour.

This may mean that a seaman is a simpler man than a landsman, more humble because more in touch with creation, less able to shut out nature, for although the seas can be damaged, they cannot yet be fully harnessed, but we must bend to them, not they to us.

To summarise then, I feel more in touch with the realities of the planet, and this is not a momentary or passing thing, but is a like the presence of a friend always with me. That is why, perhaps, that I think so much about Phlebas, a fictional character in a poem written in the early twentieth century.